In this, the second in our series of articles on the recent legislative changes impacting on superannuation, we address the implications associated with non-concessional contributions.

Non-Concessional Contributions

These contributions are typically made from savings, investments or inheritances you have received and on which you have previously paid tax.

This is a useful way of building up your superannuation fund balance – particularly in the 10 or so years approaching retirement – as one downsizes the family home or has significant surplus disposable income.

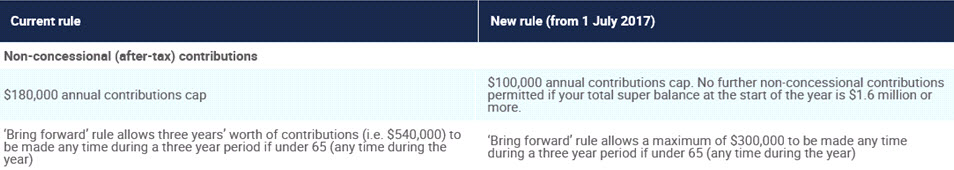

Unfortunately, the amounts that you will be able to contribute have been significantly reduced (with effect from 1 July 2017) as follows:

In addition, a superannuation balance limit of $1.6m has been imposed – after which no further Non-Concessional Contributions may be made. (This is a complex area which we will address in a separate article).

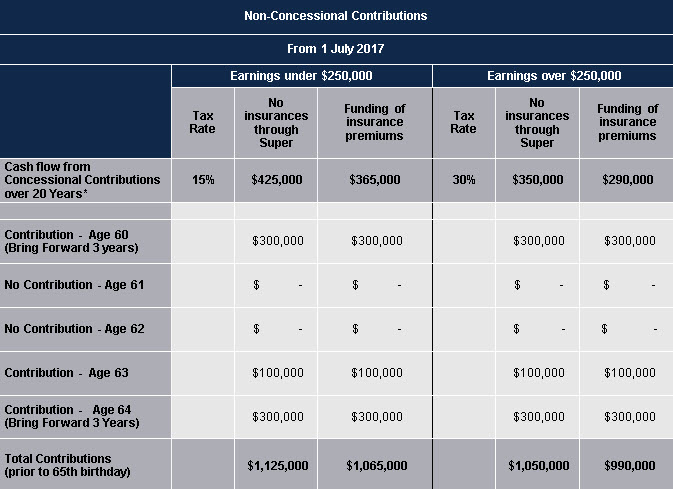

Following on from our note on concessional contributions, we highlighted that 20 years of maximising the annual concessional contributions cap of $25,000 would result in “only” $290,000 to $425,000 of net contributions to super.

It is evident from the table below, that on the basis that you had the funds to maximise both the concessional (over 20 years) and non concessional contributions (last 5 years), it may be possible for each spouse to accumulate total contributions in superannuation of between $990,000 and $1,125,000 by age 65. This does not represent your retirement balance as it excludes market growth and taxation.

* From the table in our previous communication regarding changes to concessional contributions.

For most Australians, attaining a superannuation balance at retirement capable of funding a “comfortable retirement” over one’s extended life expectancy will be very difficult unless one has the liquidity to make these contributions.

With the legislated changes in mind, this tax year is the last year in which the annual $180,000 or the $540,000 ‘bring forward” non-concessional contribution may be made.

It is vitally important to note that there are certain transitional arrangements – if you have previously contributed more than $180,000 in 2014 / 2015 and / or in 2015 / 2016.

An example follows which serves to illustrate the complexity and therefore the risk that one might breach the caps – with associated consequences:

Bruce wishes to maximise his Non-concessional contributions to super in 2016/ 2017, but only has $250,000 available to contribute during the current tax year. He anticipates after-tax bonuses of $110,000 in 2017 / 2018 and $100,000 in 2018 / 2019.

What is the maximum amount he can contribute each year over the transitional period?

2016 / 2017

• If Bruce had additional funds available – over and above his $250,000 – he could contribute a further $290,000 – taking his total non-concessional contributions for the year to $540,000.

• He would not be able to make further NCC’s until the 2019 / 2020 tax year.

• By Contributing in excess of $180,000, he has triggered the ‘bring forward” provisions. This means he has a total available NCC capacity of $380,000 for the tax years ending 2017 through 2019. ($180,000 + $100,000 + $100,000).

2017 / 2018

- His available NCC capacity is $130,000 – being $380,000 less $250,000 already utilised.

- Bruce can contribute his full bonus this year with only $20,000 remaining available for the following year.

2018 / 2019

- Although Bruce’s bonus is $100,000 in the 2018 / 2019 tax year; he may only contribute $20,000 of this bonus.

2019 / 2020

- A new 3 year bring forward cycle commences with an annual contribution cap of $100,000 – or a $300,000 3 year bring forward cap – available.

- Bruce may contribute the balance of his 2018 / 2019 Bonus – $80,000 – and any additional post tax funds up to a maximum of $220,000 ($80,000 + $220,000 = $300,000) .

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that the principal objectives for superannuation were:

- To incentivise private individuals to provide for their retirement during the course of their working lives, thereby

- Reducing the unsustainable financial burden on the Federal Government in providing state pensions to unfunded retirees.

It seems as if the latest legislation may have a positive short term impact – but a detrimental long term impact on government finances. Short termism is clearly the curse of our age – both in business as well as in politics.

Our next article will address the $1.6m contribution and balance transfer caps.