Clients considering their US allocation in 2020 may feel nervous about the macroeconomic and political crosswinds blowing across the investment landscape.

Here are five areas where the investment professionals from the Capital Group share their perspective:

1. Will there be a recession in 2020?

It’s a question that has been on investors’ minds for years now, and for good reason: Recessions can be painful. In 2019, the various twists and turns of the U.S.-China trade war and a buildup in inventories led to a manufacturing slowdown in the U.S., triggering concerns about an imminent recession.

“We have seen a tale of two economies in the U.S.: a weak industrial sector but a reasonably healthy domestic economy, thanks largely to a resilient U.S. consumer sector,” adds Spence.

The manufacturing slowdown and trade war captured the attention of policymakers as well as investors. The U.S. Federal Reserve cut interest rates three times in 2019, and major central banks around the world have taken similarly aggressive action to maintain easy monetary policy.

“It takes a while for monetary policy to have an impact,” explains Spence. “But we are already starting to see some positive signs with a pickup in the housing market. Given the low-rate environment and the health of the U.S. consumer, I believe we are going to see a reacceleration in the economy in 2020, barring some unexpected shock.”

Bottom line: Although recessions are notoriously difficult to predict, easy monetary policy and a strong consumer should keep the U.S. economy on a growth path in 2020.

2. Should I get out of the market during this election year?

U.S. presidential elections have always been contentious affairs. As we get closer to November’s general election, investors can expect divisive political news to increasingly dominate the headlines, unsettling markets. That’s likely to be particularly true this year during a hotly contested Democratic primary season, which officially kicked off February 3 in Iowa.

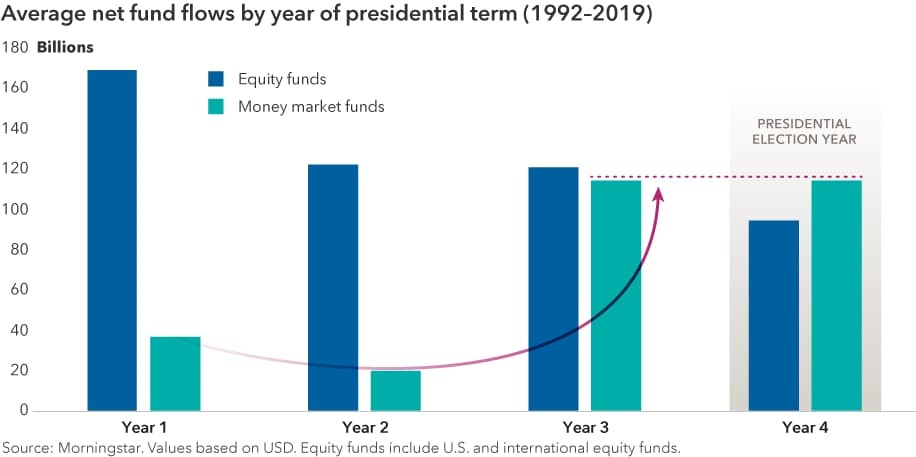

Investors may be tempted to sit on the sidelines until the smoke clears. Indeed, during previous election cycles domestic investors appear to have done just that, rotating money into money market funds during election years, then moving back into stock funds the following year.

But is this a winning strategy? History suggests otherwise. In past election years, markets have tended to return to an upward trajectory after the primary season. Stocks, as measured by Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index, have had negative returns in only two of the last 20 election years (2000 and 2008), and both declines were largely attributed to asset price bubbles, not politics

“Presidents get far too much credit, and far too much blame, for the health of the U.S. economy and the state of the financial markets,” says Capital Group economist Darrell Spence. “There are many other variables that determine economic growth and market returns and, frankly, presidents have very little influence over them.”

Bottom line: Investors who look past primary season volatility and maintain a long-term focus can succeed regardless of the election outcome.

3. Will the US continue to lead global markets?

For more than a decade the U.S. stock market has outpaced international equity markets by a wide margin, raising the question of whether this can continue.

“Investors should really be thinking of the world as one market today,” equity portfolio manager, Rob Lovelace says. “Where a headquarters is based is no longer a good proxy for where it does business. For example, many European companies are conducting much of their business in the U.S. or China. So it’s important to closely look at where companies generate revenue.”

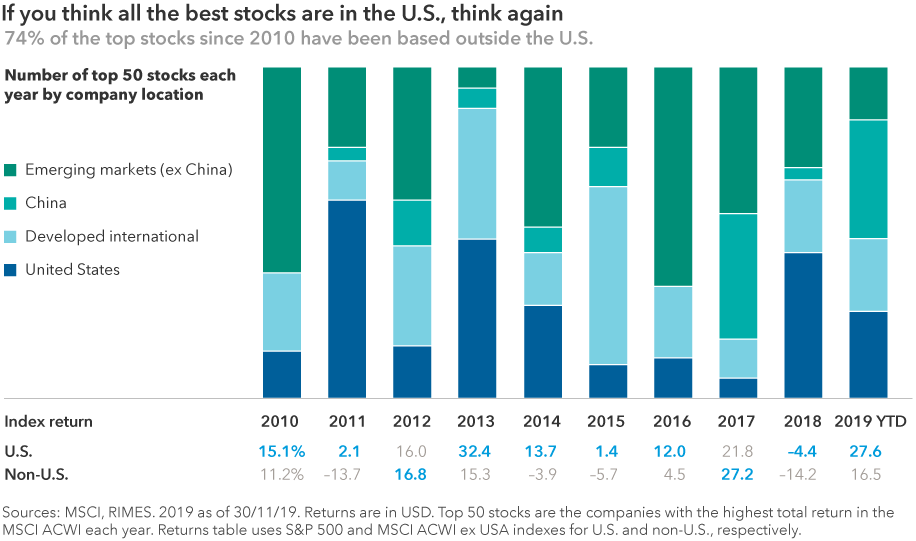

With the recent dominance of the U.S. market, a look at indexes suggests that non-U.S. stocks offer more favourable risk-return potential than US stocks. To be sure, indexes don’t paint a full picture, as differences in return can be distorted by differences in index composition.

Consider that international indexes are often heavily weighted toward companies in the financials and materials sectors, while U.S. indexes are weighted more toward fast-growing technology and health care companies. What’s more, a close look at individual companies reveals that over the last decade those with the best returns were overwhelmingly domiciled outside the U.S.

“I am finding as many or more opportunities outside the U.S. than in the U.S., even though I think overall the U.S. market will be one of the best markets going forward,” explains Lovelace. “That’s why I believe it is so important for investors to change their mindset.”

Bottom line: Even when the U.S. market is leading, many of the best-performing stocks are outside the U.S. each year, so it’s important to stay globally diversified.

4. How might the trade war affect my investments?

The global trade picture improved somewhat at the start of the year. In January the U.S. and China signed a “phase one” trade agreement in which China agreed to buy more U.S. goods and the U.S. agreed to lighten some tariffs on Chinese goods. “Clearly this is a step in the right direction,” says equity portfolio manager Jody Jonsson, who has a focus on large, multinational companies. “But we have a long way to go.”

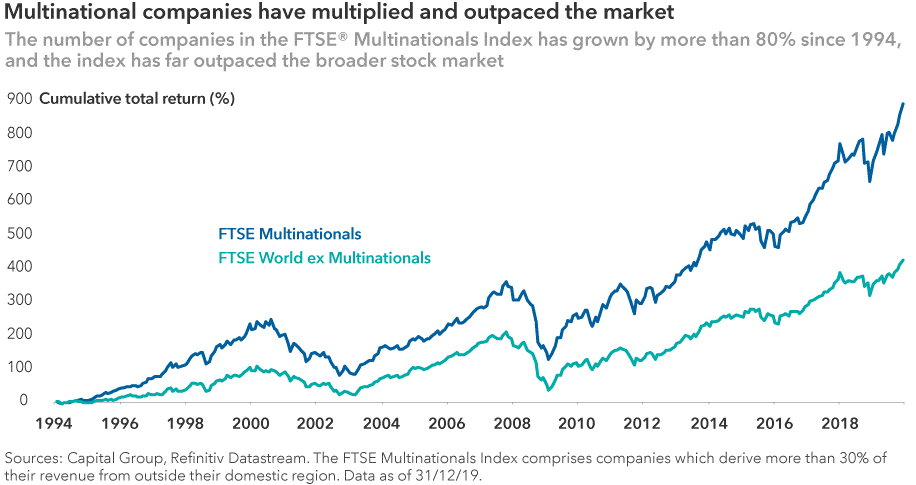

Ironing out more complicated issues such as intellectual property rights, for example, could take many years to resolve. Investors may be growing concerned that a backslide in negotiations or a further deterioration of the global trade landscape could place multinational businesses in jeopardy. “To the contrary, I believe well-managed multinational companies will be able to navigate treacherous waters and succeed regardless of geopolitical headwinds,” notes Jonsson.

In the last 15 years businesses operating in markets around the world have multiplied and thrived, outpacing the broader equity market while adapting to an ever-changing set of circumstances. Many have done so by adopting a multilocal approach, establishing successful operations in markets around the world.

“For the most part these companies are run by smart, tough, experienced managers who have seen all types of trade environments, favourable and unfavourable,” Jonsson adds. “I believe the best-run companies in the world will find ways to win even when governments are trying to rearrange pieces on the chess board.”

Bottom line: Smart companies find a way to thrive, even in a less friendly trade environment. Short-term volatility can be an opportunity for long-term investors.

5. Will negative interest rates come to the U.S.?

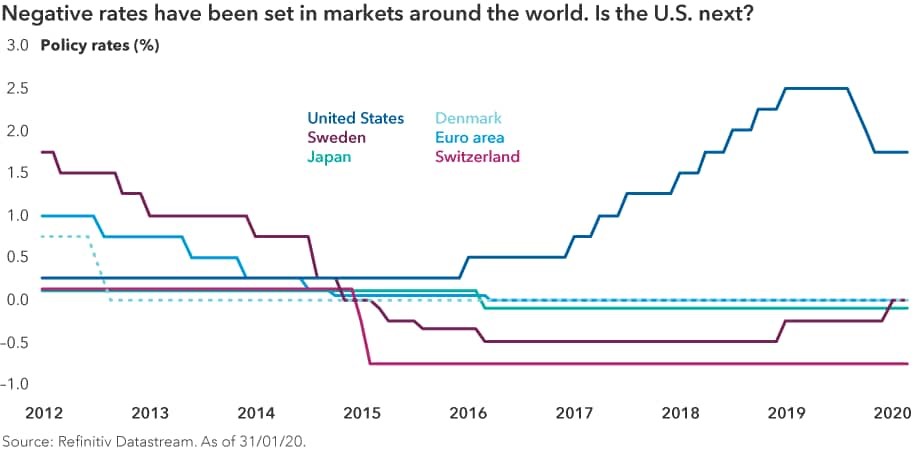

For years central banks in Europe and Japan have maintained negative short-term interest rates to help stimulate growth in their economies. Today there are more than $15 trillion of negative yielding bonds in the developed world.

So far the Fed has refused to employ negative rates in the U.S., but with the world remaining in a muted-growth, low-inflation environment, could that policy stance change? What if another recession hits?

“Negative policy rates are, in my view, a remote possibility for the U.S. over the next few years,” says Tim Ng, a fixed income investment analyst. “I think the Fed’s playbook is more likely to follow what was done in the financial crisis: progressively cut rates to zero if needed and use forward guidance as a tool. The Fed could also buy bonds, as we saw with their quantitative easing program.”

Negative yields essentially mean that investors are paying the issuer to hold their money. That generally happens during times of economic uncertainty, when buyers rush to snap up investments viewed as safe havens. While the U.S. has entered a late-cycle environment and some excesses have begun to build, Spence says the U.S., barring any unforeseen external catalyst, should remain on a growth path for the foreseeable future.

Bottom line: With the Fed on hold and the economic growth picture brightening, negative rates are unlikely to surface in the U.S.

Source: Capital Group